The Value of Education

総合政策学部准教授 ジム?スマイリ

These past few decades have seen a tremendous rise in the numbers of young Japanese adults entering higher education. Martin Trow (2007) categorised societies into three groups: those that have around 10% of their population enter higher education are elitist; those with under 50% have mass education; and those over 50% have entered the age of universal higher education. As of 2009, over 55% of 18-year-olds in Japan entered four-year universities, junior colleges or professional training schools according to Mext (Bureau of Higher Education, n.d.). Japan’s youth have more access to higher level training than ever before, but we must ask the critical question about what this universalisation means for the value of higher education in Japan.

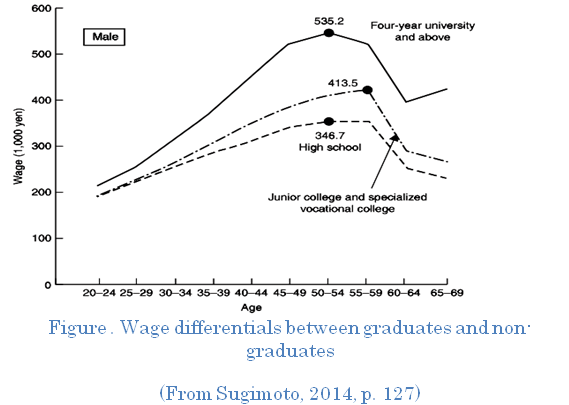

Yoshio Sugimoto (2014) draws on the 2010 Japanese census to show that still 70% of Japanese adults have not had any higher education. Japan’s elderly, in particular, are largely uneducated, a fact that keeps the percentage high. He describes the wage differences between those with a degree and those without (see figure 1). Males who have attended a four-year university will earn over 530,000 yen per month on average around the age of 50. This compares very favourably with a similarly-aged high school finisher at 346,700 yen per month. The disparity between graduates and non-graduates leads to a significant lifetime difference.

Having a higher education is still a massively great advantage in Japan, even though that benefit is less than in some western countries (Sugimoto, 2014, p. 126). But as time goes on and the universalisation of the university continues, the advantage will decrease. With more of Japan’s youth being graduates, competition between them for graduate positions will increase. Concurrently, fewer high school finishers will be available to take up the lower level occupations. More and more, these jobs will go to graduates.

The university needs to recognise this in many ways. At the pessimistic end, training students for unskilled jobs seems like a waste of resources and time for both the student and the university. This begs the question that universalisation may not necessarily be productive for Japan. There is another option, one which I sincerely hope Japan realises with gusto. Thinking only about Japan and matters inside Japan leads to an insularity that may destroy the country. As a developed country, the knowledge economy here will continue to require experts in many different areas if Japan realises her position in the world. In other words, I want the university in Japan to look outwards much more. I want them/ us to understand people as a global phenomenon and not as a unit to be measured internally to a single economy. The value of higher education will surely diminish unless the scope of consideration is widened globally.

Bureau of Higher Education. (n.d.). Higher Education in Japan. Tokyo. Retrieved from http://www.mext.go.jp/english/highered/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2012/06/19/1302653_1.pdf

Sugimoto, Y. (2014). Diversity and Unity in Education. In An introduction to Japanese society (4th ed., pp. 530–531). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Trow, M. (2007). Reflections on the transition from elite to mass to universal access: Forms and phases of higher education in modern societies since WW11. In J. J. F. Forest & P. G. Altbach (Eds.), International Handbook of Higher Education: Part 1 Global themes and contemporary challenges (pp. 243–280). Dordrecht: Springer.